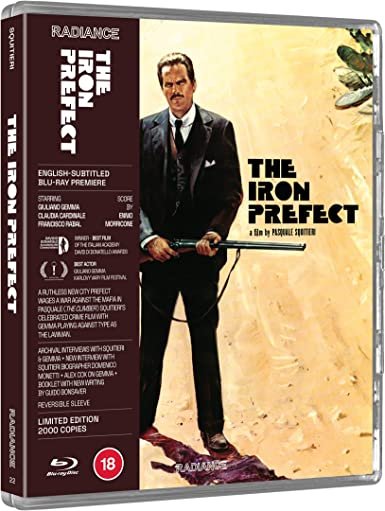

THE IRON PREFECT - Fascism and the mafia in Paolo Squitieri's film

The Iron Prefect (Il prefetto di ferro, 1977), is a film that brings together the two most powerful taboos in modern Italy: fascism and the mafia. Benito Mussolini, the idolised dictator, could not tolerate that a region of Italy should be under the control of a violent rule which wasn’t his own. Therefore, in 1925, he asked his best head of police to sort it out. His name was Cesare Mori, otherwise known as the Iron Prefect.

Paolo Squitieri’s 1977 film - which will be released in a limited blu-ray edition by Radiance Films in July - brilliantly brings the historical memory of Mori’s battle against the mafia to the screen. The extent of Mori’s success is a moot point that the film itself underlines, but there is no doubt that he used any means, legal and military, to bring the State’s rule to bear on Sicily.

Those familiar with the film may suggest that Giuliano Gemma – the actor playing Mori – feels more like a Western’s mysterious lone rider than a political drama’s grey representative of the law. But that was intentional. Indeed, it wasn’t the first time that an Italian film on the mafia had adopted the Western genre as a model. It had already happened with Pietro Germi’s In the Name of the Law, a 1949 controversial film that presented the Sicilian mafiosi as horse-riding heroes appearing against the horizon. Instead, Squitieri turned Mori into a sort of lone sheriff, something which the historical character probably was, although strictly in a starched shirt and grey suit.

During the years of Fascism’s rise to power, soon after the Great War, Mori excelled as a ruthless Prefect. He had inflexibly imposed law and order at the expense of the unruly fascist squads in the region under his jurisdiction. Mussolini detested Mori but at the same time respecting his efficient strong hand, to the point that he had him sent to Sicily, in 1924.

Beyond its Western take on the action scenes, Squitieri's film is faithful to the historical events. Mori’s success in fighting against the lower echelons of the mafia, and his difficulties in tackling the connection between organised crime and the ruling elites, are presented in a convincing manner. No doubt Mori was not the handsome, cigar-in-mouth cop which Giuliano Gemma brought to the screen. In fact, he was famous for his verbose reports and his penchant for bureaucratic detail. But the iron fist with which he imposed his authority is truthful.

His most astounding feat is the siege of the mountainous small town of Gangi, southeast of Palermo. In order to worm out the mafiosi and brigands hiding there, Mori set up something closer to a war campaign than a police operation. In January 1926, he fielded more than 800 men between police and army units to block every town's access. For ten days, the entire population was treated as complicit and had to suffer the extreme of seeing their water pipes run dry. Individual rights were secondary to the ultimate goal: arresting all the outlaws hiding in the labyrinth of tunnels dug underneath the houses of Gangi.

The part of Cesare Mori was initially offered to Burt Lancaster – and his physical presence somehow would have been closer to the historical character – but health problems forced him to give up. Giuliano Gemma, who was already famous for appearing in several action movies, from bad cop to Spaghetti Westerns (a territory explored by Pasquale Squitieri too), was central to the “glamourisation” of the Prefect. Sensual beauty was added by the star of Italian cinema, Claudia Cardinale – who by then had left the husband and powerful producer Franco Cristaldi to live with Squitieri and work with him in a number of films. In The Iron Prefect, Cardinale appears as an impassioned Sicilian peasant who eventually entrusts Mori with her son so that he can take him away from Sicily and guarantee him a better future.

Cinematically, this is probably Squitieri’s best film, well-balanced between the warm colours of the shadowy, candle-lit interiors and the open-air sequences where mafiosi are chased by policemen on galloping horses. There is only one caveat: those looking for memorable landscape shots of Sicily need to be warned that the film was mostly shot in the hilly countryside southeast of Rome.

From an aesthetic viewpoint, Squitieri’s camerawork is generally unintrusive, with little camera movements, privileging close-up shots of people’s faces, starting with the never smiling one of Prefect Mori. The editing somehow follows the rhythms of the plot, becoming particularly fragmented during the few scenes of violence.

One should also mention how the artistic quality of the film is enriched by the music score penned by Academy-award-winner Ennio Morricone. Working around the lyrics by Sicilian poet Ignazio Buttitta, Morricone composed the song “The Ballad of Prefetto Mori”, which is sung at the start and end of the film by popular folk singer Rosa Balistreri.

The film received two Donatello statuettes – Italy’s equivalent to the Academy Awards – for Best Film and Best Actor (Giuliano Gemma). It also did very well abroad, particularly in the USA. Despite this, The Iron Prefect was not selected as Italy’s entry for Best Foreign Film at the 1978 Academy Awards. According to Squitieri, this was due to the influence of Cristaldi, still fuming about Cardinale’s “scandalous” exit from his personal life.

One final issue to be explored relates to the role of Fascism within the narrative of the film. Beyond Mori’s ill-conceived disregard for the rhetoric and bombast of Fascism, it is only at the end of the film that Squitieri seems interested in bringing the role of Mussolini’s regime to the foreground. It is then that we discover that one of their leaders is involved in the high-level corruption and connivance with the Mafia by the Sicilian ruling classes. The character of the Fascist MP does not correspond to a precise historical figure but it is inspired by that of Alfredo Cucco, a fascist leader from Palermo. Cucco was expelled from the Fascist Party in 1927, following various accusations of corruption, although he eventually managed to be reinstated a few years later, when Mori’s deeds had become a distant-enough memory.

Back in Rome, Mori retired a few years later and wrote his autobiographical work, Fighting at Close Hands against the Mafia (1932) which provided plenty of detailed material for Squitieri’s historical fresco and biopic.

Cover: poster detail

Images courtesy of Radiance Films